Kate Bowler: Hi, I’m Kate Bowler, and this is Everything Happens. Look, the world loves us when we are good, better, best. But this is a podcast for when you want to stop feeling guilty that you’re not living your best life now. We’re not always celebrating our zen like mindset. I used to have my own delusion of living my best life now. I’m a Duke professor, wine and cheese enthusiast, wife and mom. Instagram gold. Then I was diagnosed with stage four cancer. That was four years ago. And I’m still here. And now I get it. Life is a chronic condition. The self-help and wellness industry will try to tell you that you can always fix your life. Eat this and you won’t get sick. Lose this weight and you’ll never be lonely. Believe with your whole heart and God will provide. Keep this attitude and the money is yours. But I’m here to look into your gorgeous eyes and say, hey, there are some things you can fix and some things you can’t. And it’s OK that life isn’t always better. We can find beauty and meaning and truth, but there’s no cure to being human. So let’s be friends on that journey. Let’s be human together.

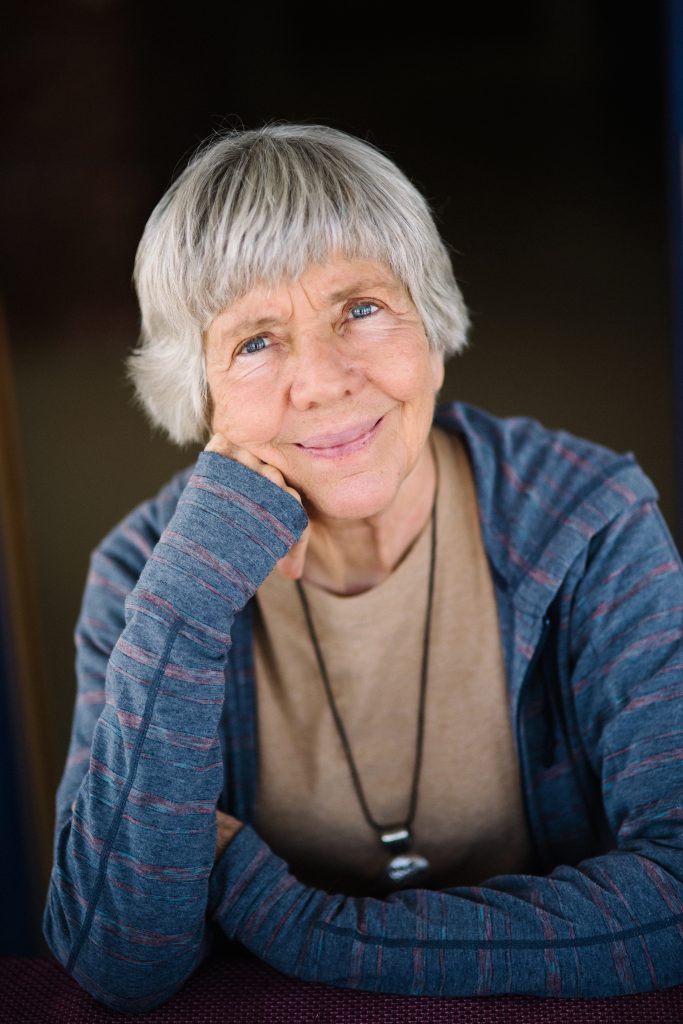

Kate Bowler: Who are we as we age? Are you the same person that you were 10 years ago? How about 20 years ago? What have you gained since then? And what have you lost along the way? Our culture has such poor language for this, the who we areness across time. The ways we grow and the things that threaten to diminish us. Our guest today knows a lot about the great opportunities and costs embedded in aging. Mary Pipher is a clinical psychologist and bestselling author of ten books. You might remember her from the bestselling book about adolescent girls called Reviving Ophelia, which my mom read to parent me. And today, we’ll be discussing her most recent book, Women Rowing North, Navigating Life’s Currents and Flourishing as we Age. She writes, with such gentleness, offering an unbelievably non self-helpy roadmap for how to age beautifully. Mary, I am so grateful to be speaking with you on this incredibly rainy day.

Mary Pipher: Well, thank you so much. That was beautiful introduction, Kate.

K.B.: Well, you’re my deep end on a question that I have sort of been, I think, inadequate in talking about, when I read your book, I was reminded of a conversation I had with my father-in-law, who’s about 70, and I gave him such crap the first time he said “life is a series of losses”. And I just remember at the time I was so worried about dying young that I think I was. I mean, like quick to dismiss the need for this much richer account of the losses embedded in aging.

M.P.: Well, of course, it’s understandable that. Hearing that phrase, especially if you were suffering from cancer at the time, would be a phrase you would resist with with all your heart. Partly, because we Americans have been taught to resist loss. We don’t think in terms of permanence. We think in terms of how do we hold out? How do we keep what we have? And of course, that’s a terrible lesson to teach us because we can’t hold on to anything. Everything is constantly changing and in flux, which is probably in some sense, what your your father-in-law was saying to you at that moment.

K.B.: You’ve played so many roles, daughter, sister, wife, mother, grandmother, caregiver of your sister. The losses we experience offer us and and seem to require us to find ways to expand our identities. So what is that look like for you?

M.P.: One of the really lucky things about I’m 72, being 72 is that I’ve had six, seven decades now to look at how the people I’m around live, to look at how other people live and to build within myself a set of skills and understandings and attitudes that allow me hopefully to cope pretty well most days of my life. So that’s a really invaluable thing about being an older person. Now, not all older people develop let’s call it wisdom, shorthand wisdom, as they age. But most of us do when we’re given a chance to grow, if we take it and if we learn from our experience and if one of our responses to sorrow and loss and pain is what did I learn from this? Then as we age, we actually have some extremely wonderful rewards for getting older. And that is one thing I wanted to capture in Women Rowing North is how much better women my age tend to be at being happy and enjoying day to day experience.

K.B.: I was kind of blown away by that, to be honest. Right? Like you write that studies show that most women get increasingly happy after fifty five. But like, that’s hard for me to understand when, as we both know, life just continues to get harder. We lose people we love. We face transitions. We, our lives shift in ways we can’t get back. Like what is the secret that kind of contentedness?

M.P.: First of all, there’s an amazing calculus to old age. And if we’re if we’ve been growing, if we’ve had our lights on, then what happens is as more is taken from us, the more deeply we appreciate what is in front of us. And so many people are noticing this during the quarantine. For example, I bet you’ve heard, Kate, that people say things like, I’ve never noticed how beautiful the birds sing. Or I have really enjoyed my flower garden this year. Well, the birds probably aren’t singing all that much louder and the flower garden probably didn’t look all that much better. But what’s happening is people are naturally making that accommodation that as they can’t appreciate and enjoy things they used to, they’re really looking very closely at those things they can enjoy. But there’s a lot of skills that make day to day living easier that hopefully as as we age, we acquire, for example, all around the world the number one thing that correlates with happiness, it doesn’t matter where you’re talking about in the world, is reasonable expectations. If we have reasonable expectations about what our lives are going to be like, if we don’t expect things to be perfect, if we don’t expect the world to cater to our needs, if we expect that every day has a certain amount of frustration in it, we’re much likely to be happier than if every time we’re frustrated if things don’t go well, we react with shock and surprise.

K.B.: There’s nothing trite about the way that you’re framing this. I mean, I’ve heard people like I’m just thinking of all the televangelists that I’ve studied over the years that that have like seven quick tips for happiness and the blah, blah, blah.

M.P.: Yeah.

K.B.: What you’re describing is a real expansiveness of life in which, you know, in the course of a single life, you expect to see your parents die, hold your grandkids, live days of joy and splendor and others in diminishment. And in all this, it requires a sort of tough mindedness to keep growing into these and through these losses.

M.P.: Absolutely. And one of the reasons I named this book, Women Rowing North, is I thought rowing conveyed certain arduous, hard work.

K.B.: There’s a lovely quote, I’m just thinking of the rowing metaphor you use. You expand on it, so beautiful, do you mind if I read you to you in an awkward way?

M.P.: Not a bit. I’d love to hear it.

K.B.: I just, it really struck me. Old age is always accompanied by loss. Eventually, one way or another, we will say goodbye to everyone we love. Eventually, one way or another, we are likely to spend more time in doctor’s offices than at concerts and more time at funerals than weddings. Maneuvering this stretch of river requires flexibility, a tolerance for ambiguity, openness for new vistas, and the ability to conceptualize all experiences in positive ways.

M.P.: You know, one of the arguments of this book is that this life stage after retirement or after middle age as we enter this this last third of our lives is very similar to adolescence in that we’re leaving behind something that’s familiar and that that’s we’ve we’ve kind of understand and have come to know and we’re entering uncharted territory.

K.B.: Yeah.

M.P.: We have in this culture such ugly, mean spirited caricatures of older women. And when I was writing the book, people asked me what I was writing about and I’d say, well, I’m writing about older women. And they would invariably say, well, I’m not old or you’re not old. They would immediately deny that either one of us was old. And what they were saying with that, no matter how old, if somebody was 80, they’d say, you’re not old. What they were saying with that is my experiences and my personality and the way I live in the world do not match up with those cultural stereotypes of what an older woman is like. And I refuse, I refuse to submit to those.

K.B.: Yeah, that sounds right to me. I mean, I’m just thinking, as a historian, there’s such an intense at least in this century, I think we’re at peak condescension for older people. There’s just an ingrained disdain, a sense that anyone older must be archaic and unchangeable in thinking. Yeah, I think there’s this great desire to sort of distance the best virtues of modernity from whatever the older generation has. And your book really reminded me of this Ogden Nash quote, my dad says sometimes which is: People expect old men to die. They do not really mourn old men. People watch with unshocked eyes. But the old men know when an old man dies. That really reminded me of watching my grandfather age and realizing that he was living in a world that had that had changed around him and whose rules he no longer knew exactly how to live inside of, because there was, I think, little little language for it and little language to give him to do it well.

M.P.: Right. Right. Well, one of the ironies is, while the stereotypes about older women are that they’re they’re in the way and talkative and and difficult to deal with, they’re needy. The actual experience of of most people that are engaged in a family or as friends with older women is that they’re that they’re very cheerful and eager to be of help and full of ideas for how to manage. And I know, for example, that most of my friends are doing, in my town some of the most important work in the community with things like prison reform or black lives matter because they have the time. You know, one of the reasons I think younger people have a hard time empathizing with the experience of older people is they’ve never been old. I remember extremely well what it felt like to be 14. And I remember, Kate, what it felt like to be your age. I had I had young children and was working full time and just barely had time to get to a toilet. I was just on a dead run from the minute I got up in the morning till I fell into bed exhausted and younger people have very little sense for the experience of older people that the prejudice is really unfortunate because it creates a lot of dread of their own aging. And it it diminishes their possibilities for friendship across the lifespan.

K.B.: Yeah. There is such a cultural preference for independence, for a sense that independent people are somehow superior, that any sort of fragility is capitulation to something that’s lesser. I’m so grateful to to hear your pitch for interdependence.

M.P.: Well, you know, it’s interesting because now, most of us, many of us are living alone. We’re living far from family. We’re not seeing very many people everyday. And one of my hopes is that what comes out of this quarantine is a renewed desire to actually be with people and to really be with them face to face, to be hugging with them, hiking with them, eating a meal with them in a cafe. But to just be physically and emotionally present in a way that we can’t be on a zoom meeting or a phone call, I think there may be a just a huge desire for this.

K.B.: Yeah. If we could recognize the great gift of, like, the great intimacy and proximity and just be able to I guess like feel our own neediness as a good thing. Like, wow, isn’t it so good to be known and to be close to people that we also happen to want them to make dinner for us. That would be nice. You helped draw a distinction that I thought was really useful between you call young old age and old old age. Can you explain that for me?

M.P.: Well, the original distinction was made by another psychologist, Berniece Neugarten, who talked about young, old age, even if you’re 95 is when you can still do most everything that you want to do and old old age you can enter at 50. If, for example, what you most love to do in life was be an editor and you can no longer read. That could be for you old old age. For example, I used to be at a really good backpacker and could hike up 14 miles and live pretty tough in the wilderness. My husband and I were backpackers and we loved it.

K.B.: Amazing.

M.P.: Well, I’m not carrying a pack up 14 miles anymore. I love to cross-country ski, I’m not doing that. I love to ice skate, I’m not doing that. And my hands, I’ve pretty much over worked from years and years of writing and cooking big meals. And when I was in high school, I was a carhop at the A & W on the highway in my town carrying those big trays down to cars and fixing them to the windows so that many of the things I used to do with my hands, such as garden and chop vegetables and write for long hours at a time. I can’t do those things anymore. And yet I don’t feel an old old age. I have a wonderful life. And what I realized is if you’re if you’re an adaptive, resilient person, there’s an enormous amount of work arounds you can do to keep enjoying life and functioning at a level that at, is really, in some ways, just as as glorious and happy as it ever was.

K.B.: So when you encourage people to build a good day, what does that mean?

M.P.: We can wake up in the morning if we’re lucky and retired and structure our days pretty much how we want. And part of having a good day is, is simply having variety. Figuring out how to have some exercise and have some friendship and have some intellectual choices and have some time when when we’re appreciating beauty. And reminding myself that whatever I have on my my list, I can approach it with interest and curiosity and an eagerness, or I can approach it with dread and that I have that choice. One of the things very pleasant about being older is the phrase eventually is no longer a word to us.

K.B.: No, totally. You describe this as like the last’s. The last time you’ll see a friend. The last time you’ll hike a mountain. The last time you’ll be able to travel, that like some people have the luxury of eventually like we keep the future hazy, as if eventually is always in front of us. But. But then it isn’t.

M.P.: There is no eventually. If I say, well, eventually I’d like to do this. If it’s something I could do, I do it. I don’t really believe in eventually anymore. Another thing is there are no small pleasures. Pleasure is pleasure. And if you can find things to enjoy, it no longer feel small, it feels beautiful. So part of building a day is simply putting together time that is enjoyable. One block after another. And knowing how to have reasonable expectations. Knowing how to modulate our reactions to the world. Knowing how when we hear bad news, we have the processes we need to deal with trauma and loss. And that we can face pain squarely. We can be honest with ourselves. We can feel it in our bodies. We can we can allow ourselves to absorb body blows patiently, just watching with curiosity the pain and then moving through it slowly across time. The harder the times, the shorter the view. And there’s sometimes that life can be rough enough that that I take it an hour at a time. I take it in whatever increment I think I can handle it, Kate.

K.B.: Yeah, I found that like the worst my life got the older my friends got, which I appreciated.

M.P.: Isn’t that interesting?

K.B.: It helps for me because I’m a historian, which means that I’m in one of the few professions where it’s assumed that your brain gets better with age and that you’ll have more to share. And. And it’s run by geriatrics, which I love. And so, you know, I’ve always been about 30 years younger than my average colleague, which I didn’t think too much about until I got very sick. And then I thought, oh, you are going to be my very best friend. And they were. They were spectacular about always showing up with the casserole, coming during any visiting hours to make sure that in the hospital I needed something. But one stage I didn’t expect is how much more fun having older friends would be, when I was trying to figure out how to love my body again after so much change, I, I wasn’t able to do those like you know, super spin, inspirational classes or anything too dramatic. And so I spent a summer working out at the local community center in the older folks, I won’t see aerobic because there was not a lot of increased heart rate. But it was great. It was great because the amount of groaning that would go on, which was so honest, like no one ever complains openly during a workout class, they just eat it. And I could look over and like, the lady next to me, Mary, would be like, oh, this is feeling weird. It is Mary. Thank you. There was such an honesty which I started to kind of get addicted to being around.

M.P.: When I was teaching at the university I go to the recreational center down at the university with mostly students and grad students and women were very self-conscious about their bodies, kind of crouched over their lockers trying to hide their bodies. And the conversation tended to be pretty stressed. A lot of women talking about relationships that weren’t working particularly well or family stress or especially body stress. Lot of women having a great deal of stress about their bodies. Well, then I switched to a gym that’s primarily older people. And in this dressing room, women walk around in their functional underwear. And their old saggy swimsuits. And there’s a lot of joking and very little self-consciousness. It’s beyond that right now. And so it was a wonderful change. And and it was a really vivid example of which of these groups is happier if you spend some time with them.

K.B.: It’s been one of the great surprises for me of this season of isolation is just realizing how much I need my parents to be grandparents to my kid. So one of the bedtime routines we have now is that my son talks to them online and I can just hear him every moment that I’m washing dishes. And it sounds like, have you ever seen a pyramid? Do you think cheese is funny? Do pirates hate land?

M.P.: How beautiful. Your lucky son and your lucky parents that they have that beautiful little interaction every day.

K.B.: It makes me feel lucky to hear. I mean, my dad is very good at holding forth. So when I could hear my son last night be like, but do you have another story about snakes? And he did have another story about snakes.

M.P.: Isn’t that funny how snakes are one of the most universal, fascinating topics to joke about? That goes back a long ways, I think.

K.B.: And just letting them need each other, which has been which makes me feel like there’s connection, there’s possibility. And that part of the great fear is that our lives shrink as we as we live in this time of like just less and less connection. I wonder, too, since you have, we have a lot of folks in our community who are, whose lives shrink a lot because of the roles that they play as caregivers. I wondered if you wouldn’t mind saying something about the roles that you’ve played as caregiver and what that’s meant to you about having to, like, discover what’s possible within a day.

M.P.: I have a younger sister who is wheelchair bound with dementia and on dialysis for about seven years, she lived nearby and I was supervising all of her care and doing pretty much everything for her. All of her paperwork and managing money and dealing with government agencies and health care and I think at one point she had about 10 docs and it was it was pretty full time job. It was essentially giving up my life in order to give her a life. And that’s a situation many older people have. At this point, my sister’s now in a very good care facility and she’s happy there. And and my relationship is visiting her once a week with some yarn and some fried chicken. Which makes her extremely happy. It’s a very easy job for me, but I think caregiving is extraordinarily difficult. I think it’s easy for people in that situation to become clinically depressed. But what I am struck by, I interviewed quite a few caregivers and I have friends now who are full time caregivers. Is something that is very rarely discussed in this culture of celebrity and in this culture where most of the attention goes to people with the big microphones. Is the extraordinary heroism of ordinary people. And how well people do when their backs are up against a wall with a partner who has, for example, severe Parkinson’s and they don’t have the money to find resources or a good facility for their partner. So they’re doing the toileting and the everything that that person needs. And somehow, in spite of the toll it takes on them, they continue to do it. So it’s it’s a really very heroic work and I used to say, when I’m queen of the world, here’s one I thing I’ll change. And when I’m queen of the world, that would definitely be one thing I would change is we would have a a culture in which people who were willing to sacrifice so much had more help.

K.B.: Yeah, that’s right. So what are some of the best gifts you’ve found as you’ve grown older?

M.P.: One of the things that isn’t often talked about, about the joys of older people is how close we are to people. How many friends we have. How much more time we have to have rich relationships with family and women friends. And I’m an activist, so, I’m in different activist communities and some of those communities I’ve been in for 35, 40 years. So I have these beautiful long relationships that extend across time where we’ve worked on certain causes together. And the relationship part is very beautiful. It’s extraordinary how many people my age describe an enhanced capacity for bliss. And at least for me, I actually find myself just being gobsmacked by bliss and epiphanies on a regular basis. Now, I think that the bliss and epiphanies were theoretically available to me all of my life. But when I was a 40 year old parent, I was moving too fast to slow down and notice. But now I actually have time to do the gratitude walks or go out on a country road and look for the neowise comet that’s in the sky tonight. And so it is a beautiful thing to just have this great unexpected capacity for bliss that often arises as we grow older.

K.B.: And the patience to look for the possibilities.

M.P.: Yes. Yes.

K.B.: That’s such a beautiful reminder. Well, thank you so much, Mary. This has been such a gift.

M.P.: Well, I’ve really enjoyed it and and it it’s a wonderful show you have, and I wish you and the show all the best of luck Kate.

K.B.: Aw, thanks so much.

K.B.: Adulthood, part two. That’s what Mary calls it, that next part of life. And it fits. Suddenly, there are no kids at home. Work no longer constitutes your daily rhythms. You may have lost a partner or live far from your adult children and grandchildren. Driving may no longer be an option. You may have outlived so many of the people who love you. Retirement by choice or by mandate may have caused you to lose work or colleagues or meaning. Maybe that Social Security check doesn’t provide quite enough of the flexibility you’d hoped for. Yes, you have lost so much. Yes, your body hurts and you aren’t who you used to be. Yes, you don’t have the identity markers that you once did that defined you so clearly. Yes, you attend more funerals than weddings. Yes, you are holding your new grandbabies as you hold your parents dying hands. Those are real losses. But what Mary reminds us is that life can still be beautiful and rich and full. In a world that equates age with liability, it’s time for a reminder that you are a gift. You give advice, you give food. You remember that thing that happened and honestly, I shouldn’t have forgotten that. You think our kids are beautiful and our bad partners should be dumped. You kept the photo album. Thank you. Even when the world isn’t paying attention, I hope you get a glimmer of a reminder that these little things add up to something that is and always will be beautiful.

K.B.: This podcast wouldn’t be possible without the generosity of the Lilly Endowment. Huge thank you to my team. Jessica Richie, Keith Weston, Harriet Putman and J.J. Dickinson. Ok, but for real, come be human with me. Find me on Instagram or twitter at katecbowler. This is Everything Happens with me, Kate Bowler.

Leave a Reply