Kate Bowler:

This is a special episode. It is brought to you by the Lilly Endowment as part of our series on Christian spirituality. And it’s a chance to have a moment to reflect on life and faith in the service of knowing and loving God. I’m Kate Bowler and this is Everything Happens.

We all want to be part of something real—not just the Netflix of it all—but the feeling that we’ve connected to this bigger, lovelier story of who we are as people, who we are as communities and countries and a world. Like, how do we align our regular, ordinary dumb lives with that feeling of the really real?

Every now and then I meet somebody who I feel like opens the door and just says, come right in. My guest today is someone who has done just that his whole life. He has been in a pursuit for what is the really real. The questions on his mind are things like: What if everyone mattered? What if dignity isn’t just something you earned—what if it’s something that you already have? What if instead of just the go, go, go, the earn, earn, win, win, shop, shop, shop of our culture… What if we actually believed—emotionally, intellectually, spiritually—in the deep belovedness of other people?

How would that change how we spend our time? Who we decide to argue with? How we show up for other people? Whether we are going to continue to have a relationship with our neighbor who makes us a little bit bananas?

If you’re not sure how to connect with that deep place, I just want you to know: this conversation is going to be an absolute delight that will inspire you and challenge you, I think, in the very best way. I can’t wait for you to meet him.

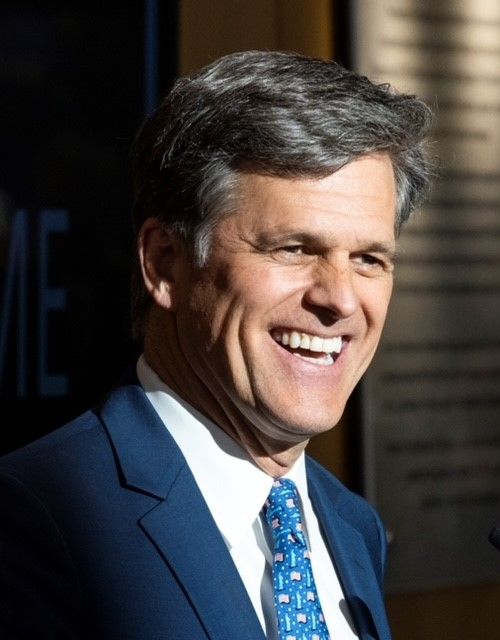

Tim Shriver is an educator, best-selling author, and all-around champion for dignity. He serves as chairman of the Special Olympics, a global movement his mother, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, began in their backyard in 1962. As chairman, Tim has grown the movement to over six million athletes in 193 countries around the world. He’s also the founder of Unite, a national initiative working to bridge divides through, you know, dignity. And in case that wasn’t enough, Tim helped start the collaborative for academic, social, and emotional learning, championing emotional intelligence way before that was cool.

He is the author of an absolutely spectacular memoir—which is also a cultural commentary, which is a greater story of how to be a person. It’s called Fully Alive. And he’s also the host of the podcast Need a Lift. And I am, as you can see, completely obsessed with him. Tim, hello. Thank you for being here. Enjoy deflecting my unmitigated admiration.

Tim Shriver:

So I’m just going to stay here probably for the rest of my life. This podcast may last decades because I’m so happy to be here.

Kate Bowler:

Oh my gosh. Well, it has been such a trip getting to know your story because you come from a family that practically invented public service. Your mom started the Special Olympics. Your dad founded the Peace Corps. Your uncle’s hella—

Tim Shriver:

Yeah, like, then the loosest term is public office for words like senator, president of the United States—just all kinds of—

Kate Bowler:

Enormous acts of heroic leadership. So I wondered, is there some kind of unspoken assumption growing up as part of your family that service was just in your DNA?

Tim Shriver:

Well, I mean, yes, I suppose that it’s fair to answer that question: yes, service was in our DNA. But we didn’t think of—I never thought of it as service. I just thought of it as what we do. On the weekend, our house fills up with Peace Corps volunteers. During the week, our house fills up with people with intellectual disabilities who are learning to swim. And early in the morning, my dad gets up and goes to mass and we go with him at 6:45. That was just the way we grew up.

And I mention that not to brag but rather to say that a lot of times the concept of service carries with it a lot of guilt or responsibility or duty. You should, Kate. You know. You have so much—you ought to be of service to others. That’s not the way that we felt.

Our experience, both with our parents but also independently, was that this was the most fun thing you could do. I mean, this was the most exciting thing. This was work that mattered. This was a way to touch the heart and soul and power of life.

My parents embodied the idea that connecting with people across divides, finding ways to empower them, lifting their voices and their experiences to a point of dignity—that was really livin’, you know? And so that’s kind of what it was like.Kate Bowler:

I just really like thinking about how much you wanted to find your own place inside this story on your own terms. When you started your career as a teacher in Connecticut, it sounds like young Tim was really hungering to figure out how you were going to find that relationship between meaning-making and your own job slash calling.

Tim Shriver:

I did. And, you know, I grew up—you mentioned the politics in my family—both of my parents and my uncles and aunts and grandparents were involved in kind of the political side of making a difference. The great speeches, the great exhortations, the great public policy transformations. Could you pass a new law? Could you change an existing law to more fairly and more hopefully empower people who were on the margins of society? These are the big ideas.

For me—I couldn’t have said it then—but I somehow wanted to actually know the people. I didn’t want to know the issue. I wanted to know the person.

And so I didn’t have a plan, but a friend of mine—like I was in my junior year in college—and he said, “Have you ever thought about taking any of the classes in teacher preparation?” I was like, “No.” He said, “Well, you should try it. Try one of the classes this semester.”

So I went over and there was this—when I was in college you could shop a class for the first week—and I shopped the teaching class. And I thought to myself almost immediately, huh, this actually would allow me to actually meet and know and understand another person.

Teaching is, you know, it’s not like social work, it’s not like medicine, it’s not like other helping professions. You live together with people for somewhere between 10 months and sometimes two or three or four years. If you’re in a high school, you see the kids over and over again, you meet their families. If you’re ambitious, you do home visits. You do weekend activities, you go to games, you watch shows. I mean, you really get to meet and know and understand—if you are curious—the lives of other people.

And hopefully you get to make a difference. That’s certainly what I thought. And so it seemed like a perfect place for me.

Kate Bowler:

What did those early years teach you, do you think, about who gets to matter?

Tim Shriver:

Well, I think the first thing I learned was probably a function of me being naive. I guess I just thought everybody’s wonderful, you know? Like, folks who are on the margins are wonderful and happy and excited, and they just don’t get a chance.

Well, that wasn’t true.

My students came from a small city, but it was a poor city. It was the seventh poorest city in America at the time, New Haven. They were angry. They were frustrated. They didn’t trust people. They didn’t have a hopeful view of the future many times. They often were cynical about the intentions of teachers like me. Really? You care? Are you sure? How long are you gonna be here for? You know, really good, tough questions.

These kids were dealing with really, really brutally difficult life situations. But they brought me closer to the capacity to tell the truth about the pain they were feeling. And therefore to meet them where they were. They wouldn’t let me meet them in some more ethereal or conceptual or politically oriented way—like, “Let’s create opportunity here.” No, no, no.

First, you’re gonna have to understand, Tim. Mr. Shriver, first you gotta tell the truth: “I’ve come up in a place that’s not fair. I came up in a place that treated me horribly. I’m coming up through foster care. I’ve been up with family situations that are brutal.”

And if you can see that, then we can talk.

That was jarring, but ultimately a great education for me.

Kate Bowler:

Because sometimes it sounds like we feel like we’re—you know, I wanna be in the economy of knowledge with you. Like, I’m a knowledge worker and you’re a knowledge-needer. Look, we’re good to go. But you were pulled into this economy of love and—

Tim Shriver:

It’s an economy of relationships. I mean, you know, Jim Comer, who I did a fellowship with when I was 25—he was working at the Yale Child Study Center, a child psychiatrist working in school reform—he said the main thing you have to unlearn about education is that it’s about information.

And the main thing you have to learn about education is that it’s about relationships.

And you will learn this from your students because they don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.

But he reminded me—or actually taught me—that the primary mechanism by which learning takes place is relational. It’s almost like there’s a pipe from you to me or from me to you. And that pipe is the relationship. And knowledge can flow through it. But if there’s no pipe? You can be talking about the periodic table or the dates of the Civil War or the importance of To Kill a Mockingbird as a piece of literature, or you name it… but the kid’s not going to learn it if there is no pipe.

If they don’t trust you, if they don’t have confidence, if they don’t want to be a part of your life, if you don’t want to be a part of their lives, they’re going to be disengaged.

So it was really unlearning that teaching was about transferring information, and learning the critical work of trying to build relationships.

Tim Shriver:

…Which, you know, great teachers have always known. There was really no science of it, and we didn’t talk about it in teacher preparation classes, even in psychology classes or educational psychology. We didn’t really talk about, you know: How do you build strong relationships? How do you build strong empathy? How do you develop listening skills? How do you develop self-regulation? How do you develop truth-telling skills?

I mean, those were all skills that I had never heard of until I was in education for about five or six years. And we started working in this whole area of what we ended up calling social and emotional learning. And then things started to change. We began to build a kind of science around this. And it’s been very exciting.

Kate Bowler:

It also sounds encouraging for people who are considering volunteering or mentoring or just trying to be involved in teenagers or young people in any way—like actually you being a well-regulated, loving, and caring adult is probably as important as your memory of long division.

[short break for sponsors]

Kate Bowler:

The heart behind the Special Olympics is a very long story for you, though. And it stretches back to your Aunt Rosemary. I wonder if you could start there and if you can tell me about her.

Tim Shriver:

Well, my Aunt Rosemary was born in the early part of the 20th century. My grandparents were already successful when she was born. They were growing a big family. Rosemary was in the beginning stage of that family—they went on to have nine kids. Boston. Irish. Catholic.

Kate Bowler:

I feel like you’re just using nouns to explain it. You’re like…

Tim Shriver:

You know, it’s a model. I think a lot of people go, “Oh, I get that.” You know what that looks like, sounds like.

But Rosemary was different from birth. And she had what we would today call an intellectual disability. We’re not exactly sure of the causes, but we do know that at that time it was a source of enormous shame and embarrassment for a family.

And many, many American families—and many families in other countries—were told to give up their children with an intellectual disability. Just put them in an institution. Get rid of them. Mothers were told, “Move on. You’re going to harm your other children if you don’t let this child go. This child’s useless. This child’s hopeless. This child has no value. Start over, have another baby and move on. This child will be taken care of by professionals,” so to speak.

My grandparents chose to keep Rosemary at home. Which I think was the most important decision of their lives. Because that meant that my mom and her brothers—John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, Ted Kennedy—and her sisters, Jean and Pat and Kathleen and Joe and Ted… all these children would grow up with a sister who the world didn’t understand and didn’t love and didn’t care about.

They had to. They were sitting at the dinner table. Rosemary never went to school. Rosemary didn’t have friends. Rosemary didn’t have playdates. Rosemary didn’t go to birthday parties. Rosemary didn’t join teams. But there she was with her brothers and sisters every day.

So I feel like I can almost look at that dinner table and know what my mother later came to tell me—which is that it made her furious. That she loved this beautiful sister and the world didn’t.

So she wanted—really with her whole life—to prove to the world that the world was wrong. That Rosemary wasn’t wrong. The world is wrong about Rosemary.

And so that led her to embark in her 20s and 30s and into her later professional life on trying to find ways to change life for people with intellectual challenges like her sister.

Even though Rosemary was hidden—President Kennedy ran for president. No one knew about Rosemary. She wasn’t publicized. There were hundreds and thousands of pictures of President Kennedy with his wife, Jacqueline, his children, his sisters, his brothers, his parents—none with Rosemary.

Until, in 1962, my mom went to the president and said, “I want to write an article and let the world know you have a sister with an intellectual disability.” And she wrote it and put it out in the most public environment possible—which at that time would have been The Saturday Evening Post—where she authored an article talking about the camp she was running, but also talking about her president and her own sister, Rosemary, and saying that this should no longer be a source of shame to families. That families could be proud of their children, no matter what.

And you could hear the echoes of a religious message: Every child. Not some children. Not smart children. Not fast children. Every child is born a child of God. Every child is a gift. It’s not conditioned on any skill or any criteria that we use to evaluate whether you’re good or bad or desirable or undesirable or valuable or valueless. No, no, no. These children matter.

And that’s, in the end, what the Special Olympics movement became—was another way to prove that point.

Because all of a sudden, a child with Down syndrome isn’t a person with a disability, isn’t a person with a low IQ, isn’t a person with speech challenges… He’s a point guard. He’s a striker. He’s a freestyle swimmer. He’s a marathon runner. She’s a sprinter. A long-distance runner.

And it seemed like, almost intuitively at the beginning of the Special Olympics movement, that sport could do what other things had failed to do. It could get people to shift how they see—not what they see, but how they see.

And that became kind of what I learned a lot about when I studied theology and studied religious experience and studied spirituality later in my life—was like, Oh! That’s the big deal. Not changing what you see, but how you see. How can you put on—in the language of the Christian scriptures—the mind of Christ? Not the work of Christ or the belief in Christ or the creed of Christ. The mind of Christ.

That’s kind of—what I would say almost directly—what the Special Olympics movement still does today for millions of people. And you know, it’s a practice. It’s not like you learn it and then you’ve got it. You’ve got to practice.

So anyway, Rosemary inspired my mom. My mom inspired me and my four siblings. And today, the movement inspires tens of millions of people every year.

Kate Bowler:

I’ve heard you say just how frustrating it can be when there’s one particular kind of response to the Special Olympics, which is like, “Service is nice. People want to be nice. It’s nice to help people.”

“Oh, I work with the Special Olympics.”

“Ohhh, that’s so nice.”

Tim Shriver:

Yeah, “You’re such a nice…”

Kate Bowler:

“You’re such a good person.”

It really started to bother you. And I kept thinking about that, because your argument seems like: that service is not just nice. It’s transformative. Like, we’re talking about the grittier parts of actually being fundamentally changed by the people around you.

And I—I know that that’s a change in my own thinking. I really used to think, God makes lists of people: like, the sick, the poor, the unfortunate… you know, the widow, the orphan… that there are lists of people. And it’s my obligation to be a good person, to help them. Because we’re mandated by God. And that’s just a part of my slow work of sanctification.

And then when I got very sick, and I started spending so much more time in hospitals, I just—I realized that it’s not like “I have to, it’s a place where you go to be good.” It’s a place you go because that’s where God is. Like you actually get to be in a place where you feel… just what you’re describing—where there’s a clarity of beauty. There’s a crispness to my “underside of the universe” feeling that I wouldn’t get if I didn’t go there.

I just—I felt like you’d agree with me on the “it’s not… that’s not nice.”

Tim Shriver:

No, I think, Kate, it’s a huge point. And I think actually our country and our culture is trying to figure out how to reinvent what we would have called “service.” My dad would have called—or my mom would have called—“volunteerism” or “national service” or things like that.

I think we all know there’s something good there, but we all also worry about—wait a minute, is this like rich people helping poor people? Is this like… patronizing? Is this… nice? That doesn’t feel quite right.

We’re trying to understand what you’ve just described. Which is that in the vulnerable places—as I hear you—in the vulnerable places in life, a lot of the baggage that we carry gets peeled away. A lot of the scales kind of fall from your eyes.

“Oh, wait a minute now. This is real. This is life and death. This is love. This is not trying to get ahead. This is not trying to get your hair to look better. This is not trying to get a promotion. This is not trying to buy a new car. This is real.”

What those kids taught me: this is real.

And what you describe in the hospital: “Wait a minute. Now this is the place where many of the distractions are eliminated.” Unfortunately, great suffering seems almost like a fast track into the presence of the Divine.

I don’t know why God designed us that way, but it seems almost irrefutable.

Kate Bowler:

Isn’t it Richard Rohr who said, “The shortest path to God is love and pain”?

Tim Shriver:

Yeah—great suffering and great love. That’s exactly—that’s Richard. And I think he’s right.

And so great love does allow us to almost see the heart. You might almost say: to see as God sees.

I’m going to say something that sounds a little bit too comprehensive, but I would say that of the thousands and thousands of people I’ve met who volunteered or came to the Special Olympics movement, every single one of them says: “I got back more than I gave.”

I used to spend a lot of time—I would ask people, “What did you get back?” Because that’s different than, “I should give to become sanctified,” right? Or “I know God’s got this checklist, and if I give again today, I’m going to move up the checklist.”

No—what do you get?

I’d leave that to your listeners and to your audience to think through. What do you get back when you give? Because my sense is, from listening to people tell the answer to that question, that they get back something deep within themselves. They get back some sense of connection, some sense of hope, some sense of possibility, some sense in which they’re seeing something more true. That they’re getting into the God zone—even if they don’t use that language.

Kate Bowler:

Yes. Yeah. And it does have some relationship, I think, with witnessing vulnerability. Being really up close to something—that delicate space where you watch somebody need something. You watch someone try.

Like in the hospital, for me, it’s that feeling that in the moment of panic or desperation—when you have to physically have someone do something for you that’s humiliating—and that person… they’re like the warm hand. The hand on your head.

Like the everyday miracles of being cared for and feeling yourself fall into the gratitude of being put back together.

But when I was hearing you describe the moments in the games, I got so teary thinking about this one story—I think it was in Ireland—and it just took 15 minutes for one athlete with serious limitations—was it to like move a…

Tim Shriver:

A beanbag, yeah. Donal Page. Yeah. I can still see the whole scene in my mind’s eye.

Tim Shriver:

You know, we’re there and it’s like a thousand people in this small arena in downtown Dublin, and the president of Ireland was there with me. And Donal comes out in his wheelchair.

I learned later his backstory—that he’d had the last rites of the Church, he’d almost died several times in infancy as a little baby—18 months, 20 months old. And he’d grown up his whole life not able to speak, not able to control his hygiene or his body. But he was loved by his family. His dad was a dairy farmer. His brothers and sisters—I think there were seven of them.

Anyway, he comes out. I think he was maybe 16 at the time. And his job is to lift a beanbag. This was his contest. This was an event at the Special Olympics games there in Ireland.

There was this awkward pause at the beginning because once the announcer said, “Donal Page, you may begin,” he kind of looked around the room and you could see he was trying to move his hand—and he couldn’t move it. You know, so he couldn’t get the hand to just pick up the bag. He’s trying. His shoulder was sort of lurching a little bit. And the place was just deathly silent. You could hear a pin drop. Everybody’s embarrassed. This is awkward. We’re all staring. He can’t do it.

And about the three-minute mark—which is a long time—his hand finally gets to the bag. It sort of gets on it, and he grasps the bag. And you can hear a couple of people: “There you go, lad!” You know, cheers.

I talked to his dad later, and he said, “You know, I was watching him in the back, and I always tell them, ‘The doctors don’t know what he can do. Just give him a bit of time.’” And he said, “I was just hoping the people would give him a bit of time and we could do it.”

Anyway, Donal picked up that beanbag. And it took him another 15 minutes to lift it and cross it from the right side—facing his side—right side of the tray in front of him to the left side.

And by the time it was about halfway across… the place was just in a roar. I mean, people were cheering like it was the finals of the World Cup. People on their feet. I look over at the president—tears are coming down her face. Tears going down my face.

He puts that beanbag down, and I thought to myself, I will never in my life see a greater athletic performance than I just saw. You can have the greatest stars of soccer or baseball or football or hockey or tennis or you name it—gymnastics, skiing—I don’t care. I mean, they’re great athletes. Don’t get me wrong. I love watching sports. But I’ll never see an athlete any better than him.

And there you have the moment.

This is not someone who was given anything other than his heart and his soul and his giftedness as a child of God. And that’s all he’s got. And he’s using it.

And people look at it—I look at that and I go, Oh my… You know, if we were living in biblical times, the prophet would take to writing down the story and say he was a witness to the presence of God. In my view, that’s the way I see it.

Kate Bowler:

Oh, I love that so much. It’s so beautiful.

To watch it—just—it does, it feels like you’re close to a miracle. Yeah. Because it creates genuine awe to see someone reach up to the very edge of what they can do… knowing that they might not.

Because it’s the knowing that they might not be able to get there, knowing that any of us might not be able—to know what it’s like to fully try. It lets you know something about somebody. It lets you know they’re… they’re courageous. And that they’re… it’s kind of just beautiful.

Tim Shriver:

Beautiful.

Kate Bowler:

They’re beautiful in the attempt.

Tim Shriver:

I mean, you know, in the old theology, it was human beings seeking the good, the true, and the beautiful. The good. The true. The beautiful.

And you know, I think a lot of theology is about the good. You know, the more cerebral versions of theology are about the true.

Kate Bowler:

That’s my job. We’re not going to take that away from me.

Tim Shriver:

I mean, there are a thousand courses in moral theology and ethics and stuff like that. There are a thousand courses in the true—Was Calvin right? Was Luther right? Was Augustine right? Was Thomas Aquinas right? You know, all that kind of stuff. That’s the true.

There’s not that many courses in divinity school about the beautiful.

Kate Bowler:

Yeah, that’s right. That’s right.

Tim Shriver:

But Donal taught that course. You didn’t need it. You don’t need a professor any better than him.

Kate Bowler:

Actually, I have one professor friend, Jeremy Begbie—he does these musical lectures. And I—I really learned something about God from hearing him play slash perform slash speak.

But he described the metaphor of God not as spatial—like “more of God, less of us”—but entirely sonar. Like that the more of God there is, then the more of us can be like rung, like a bell.

And sometimes in those moments—like when you see someone do something—it is kind of like you hear a bell being rung and you realize, like, “Oh my gosh,” and then we’re all of the same stuff.

Tim Shriver:

Beautiful. And there’s another way of thinking—and that’s what the music probably does for you, or that’s what Donal did for me—dropped me out of there and into, “Oh wait a minute. This is another mode of perception.”

I’m no longer seeing a person with a disability. I’m seeing a beautiful human being. It’s very different.

Kate Bowler:

Oh my gosh, that’s—that is genuinely what cancer did for my thinking.

Because now—because at first it was: I am separate. I am in pain. I am being taken apart. I can now no longer climb the ladder or walk at the speed of ambition, et cetera, et cetera.

And then the second I had to drop down to that other place… well, it turns out most of the rest of us are here.

And I went from being actually quite lonely to feeling in that one way, like the never aloneness.

[brief music and sponsor message break]

Kate Bowler:

I really, really, really like your theological brain.

Tim Shriver:

No—you know, I just want to be clear: no one has ever said that to me.

No one has ever said, “I like your theological brain.”

Thank you. I appreciate that. I like yours too.

Kate Bowler:

When I was in my Master’s program, they made us take a whole year of systematic theology. And I just—it was kicking and screaming for me the whole time.

But by the end, what was so helpful to me is it did give me a feeling of the whole chessboard. And what a joy it is to just—over the course of your life—have different stories about ourselves and about God to reach for.

Like, when I hate myself—actually, isn’t there a story about creation maybe that I need?

When I feel too busy to help others—is there actually a story about transformation that maybe I need to remember and spend less time doing my hair?

Tim Shriver:

Yeah. Maybe it’s not spending less time doing your hair.

Maybe it’s just doing your hair with a little more love.

Like, when I look at my hair and I think, “God, it’s so gray. Jeez, it’s out of place. Why doesn’t it ever sit…” Like right now, it’s okay—but I’m judging myself.

Kate Bowler:

All the time. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Me too.

Tim Shriver:

I’m actually being mean to me.

Kate Bowler:

Always.

Tim Shriver:

But if I’m kind of in a better place, if I’m a little more centered, if I’m a little more in touch with my—

I can look at my hair and think to myself, “Oh God, that’s okay. It’s kind of okay.”

And then I can still comb it, and maybe I can dream of it being darker—but I don’t dream of it being darker with quite as much fear or hostility to the fact that I’m a 65-year-old dude who’s got gray hair. I mean, that’s just what I am. That’s what that looks like.

Kate Bowler:

I wonder—you’ve been doing this work for such a long time. You’ve been Chairman of the Special Olympics for maybe three decades. Is that about right?

Tim Shriver:

Yeah. Almost 30 years. Yeah.

Kate Bowler:

I wonder, over the course of those decades, what has changed the most in how the world sees people with disabilities—and what still breaks your heart?

Tim Shriver:

That’s a really good question.

I think in many, many countries, you see millions of people now who celebrate people with intellectual disabilities. I mean, we’re seeing people with Down syndrome in television ads. We’re seeing them in marketing campaigns. We’re seeing them in films. We see people in open transportation. We see moms and dads—who I would dare say are proud of their kids. Which I could not have said 30 years ago. I couldn’t find a mom or dad who—they might’ve been proud, but they were never given a chance to brag.

Those chances exist now.

In the whole world of tolerance and diversity—it sounds a little political—but I think our community has been enormously privileged to be a part of the change that has come by reducing our fear or anxiety about difference.

What’s still the same?

What’s still the same is most of the time, it’s very lonely and very isolating to have a disability.

Most of the time—I was just talking to a friend of mine whose son—actually, my godson—is 22. Smart. Wonderful. Charming guy. He hasn’t been invited out by a friend in two years. Can’t get a job. Lives at home. Really struggling. Really struggling.

So the deep attitudinal barriers… I don’t think people willingly let them crop up, but you know—we’re hearing again now recently, people using the word “retard” to mock people. People in political life and prominent positions. Wealthy people.

Elon Musk posted some time ago that he wanted to make it okay to use the word “retard” again. That was the message. I don’t think he means—

I don’t know. I’ve never met Mr. Musk, and I know he’s a man of great achievement in many respects.

But… do we still have to use words like that? That humiliate our community? That make people feel like they don’t matter? That make people feel like they’re never going to fit in?

Do we have to use that language to make a political point?

Do we—do we have to…? It’s just so negative.

You know, if you’d asked me when I took this job what the biggest challenge facing Special Olympics was, I would’ve said: negative attitudes, discrimination, bias, humiliation, disdain.

If you asked me today, I’d say the same thing.

Kate Bowler:

This is just a very tender time for families who are worried about supporting their kids. Having enough. Just—we’re going to probably need a greater degree of awareness and compassion in these coming months and years.

Tim Shriver:

Yeah, well, our community gets swallowed up in larger narratives.

You know, “I want to cut federal spending.” Okay. That’s fine. I’m not either for or against it.

“I want to reduce waste in healthcare.” Yeah, okay, good.

And then the sweeping regulations get passed, and who gets put out of their house?

A 32-year-old with Down syndrome.

Who gets denied a home healthcare aide?

A person with complex disabilities.

Who gets reduced in the amount of support they get in school?

The aide they had in school to help them navigate classes?

The child with autism.

And the list goes on.

But people don’t, you know, they don’t see it. They think, “Oh, we passed a bill, and we’re going to save this,” or “we’re going to change that,” or “we’re going to add this,” whatever.

I mean, your politics is up to you.

But our community is really so often hidden.

I’ll tell you a quick story.

The law enforcement community has been one of the great supporters of Special Olympics. And I was with a law enforcement officer who was very graciously driving me around to the games in Nebraska a few years ago. And he’s kind of kidding me. He says, “You know, I bet you’re—you’re like a Democrat, aren’t you?”

And I’m like, “Well, you know, yeah, Special Olympics—I’m no party.”

He says, “Well, you probably like all that healthcare reform.”

And I said, “Well, I’m not a student of healthcare reform.”

He says, “Well, do you like that Obamacare?”

And I said, “Well, I like the fact that it makes it impossible to deny healthcare to people with pre-existing conditions.”

He said, “What do you mean?”

I said, “Well, the law up until now—a person with an intellectual disability could be denied healthcare. But that law makes it illegal to do that.”

And he said, “If I’d known that, I’d have been for it.”

So our community—we’re small. Our moms, our dads—they’ve got so much work to do. It’s so difficult. Our self-advocates are fighting so many things. We don’t, you know—we don’t have a huge PAC. We don’t have billions of dollars. We don’t influence voting patterns.

So we get swallowed up in these larger debates. And people don’t even know how these changes affect our community.

We just have to do a better job.

Because I think most people are good. Most Americans want to be supportive of our community.

But a lot of times, the bills and the laws and the rules that get passed are devastating. And it’s very, very painful.

Kate Bowler:

You’ve been so practical about this—your work with the Dignity Index, trying to help people learn to disagree better.

Tim Shriver:

Well, you know, what I found out in Special Olympics—when I distilled it—what I realized was that people’s hearts and minds were changed when they treated someone with dignity.

When they didn’t see the person as broken. Valueless. “Disabled person.”

They saw the person as an athlete.

There was a switch.

So I thought to myself, “Why can’t we do that switch with Republicans and Democrats? Or with Black, White? Or rich, poor? Or gay, straight? Or Heartland, Coastland? Or farmers and urban dwellers?”

Why can’t we have a similar switch?

Because it doesn’t mean we’re going to agree on everything. It doesn’t mean we should. I don’t really think agreement is necessary.

I just say: differences of opinion are not a problem.

There are 300+ million people in the country. That means there are 300 million opinions. That’s democracy.

That’s actually not the problem—that’s the solution.

Getting everybody’s opinions is the solution to our problems—not the problem.

But you can’t get to a solution to the problem with many opinions if you treat people with contempt. If you write them off. If you call them names. If you think you’re superior. If you label them “evil”—whoever they are: Democrats, Republicans, urban dwellers, rural dwellers, college-educated, non-college. “They’re the problem”? Really?

Are you sure?

So the Dignity Index—we were playing around with: what could we do to bridge these gaps?

So we built a scoring tool—because we thought, if you could score people—

Kate Bowler:

Yeah, you want to have more dignity. Yeah, yeah.

Tim Shriver:

Yeah, yeah. If you got a bad score, you go, “Oh, dang. I want to score better.”

So we built this scoring tool. It’s called the Dignity Index. People can look it up. It’s very easy to learn—you can learn it in literally minutes.

And it allows you to see how you score when you disagree with someone.

So from a 4 down, like a 4 is, “Our opinion’s better than your opinion.” A 3 is, “We’re the good people. After all, Kate, you and I—we’re interested in theology. Those people? Like secular people? Not so good.” That’s 3-language.

A 2 is a little different. A 2 is, “No, it’s not us versus them. It’s us or them. They’re bad. They’re evil. Those people have to be destroyed. We’ve got to get them.”

And 1-language is violence. “They’re not human. They have to be eliminated.”

A 5 and up—a 5 is sort of like “equal time.” Okay, you and I don’t agree on everything. You get your minute. I get my minute.

A 6 is, “Wait a second. We don’t agree. Let’s see if we can find places of agreement.”

When you get up to a 7, there’s a certain humility: “Wait a minute. Maybe I’m passionate. Maybe I’m strident. Maybe I believe. But maybe I have something to learn from where we disagree. Maybe I need to understand your story better.”

And an 8 is, “No matter what. No matter what you’ve done. Even if you’re in prison for life. I’m going to treat you with dignity. Even if you’ve committed terrible crimes.”

The scoring thing—we thought was going to help people go, “Okay, Candidate X, you’re running for the Senate. You got a bad score last night.”

Actually, people have been almost completely uninterested in using it for politics, which is what it was designed for.

Kate Bowler:

Oh.

Tim Shriver:

But they’re really interested in using it in their relationships—with their Uncle George, who they don’t want to have at Thanksgiving.

With their coworker, who they really don’t agree with and just feel is making huge mistakes.

They really want to use the Dignity Index at work—

“How do we build a team here where we don’t call each other names?”

Where the managers don’t yell at the people, or the people don’t yell at the managers.

How do we use this in our faith-based institutions?

Because the divisiveness in our country is in our churches, in our synagogues, in our mosques.

How do you use it in school?

By the way—if you’re listening to this and you’re hearing, “Wait a second—is he telling me I should compromise with those horrible people?”

No. I’m not telling you to compromise. I’m not telling you to mute your principles. I’m not telling you not to hold people accountable.

You should do all those things. Hold your principles. Hold people accountable. Speak your truth.

But add one principle.

Treat the other person with dignity.

Don’t humiliate or be contemptuous to other human beings.

You can be very strong about their policies. I’m very passionate about believing that people with intellectual disabilities ought to have good, full, fair, and equal access to education, to housing, to transportation, to employment.

I will not compromise. You can’t get me to change my mind—I don’t think.

But I do not have to—if you say to me, “Well, those kids shouldn’t be in school,” I do not have to say, “You’re a horrible person.”

What I can say is: “Here are the programs. Here are the policies. Here are the outcomes. This is why I believe what I believe. Can I help you try to understand my point of view?”

And that’s more likely to bring people to your side.

This is the secret of the Dignity Index: people don’t see their own contempt.

But it makes an enemy for your cause.

The more contemptuous you are of the other side, the less likely you are to convince them to change their mind.

Kate Bowler:

Oh my gosh. That’s so good.

It’s so practical.

I can think of so many applications.

My solution has been offering to pay my brother-in-law $10 for every podcast he doesn’t listen to that I disagree with.

Tim Shriver:

Well, that’s actually quite practical.

That’s not telling your brother-in-law that he’s—

Kate Bowler:

No—it’s ten bucks. One episode.

Tim Shriver:

That’s not telling your brother-in-law that he’s evil.

That’s just saying, “Look, I’ve got a new incentive structure for you.”

And I haven’t heard that one before, you know—but that’s not a bad idea.

I mean, a hundred million Americans have ended relationships in their own families. With their closest friends.

My daughter—one of her best friends from high school married someone from a different political party. And two of her friends refused to go to the wedding and said, “I’m never going to talk to her again that she married that guy.”

We have it in my family.

So, you know, it’s really—maybe ten bucks to not talk about politics, or ten bucks not to listen to a podcast would have been a better solution.

Kate Bowler:

Tim, I feel like you’re always just trying to talk us into taking those extra small steps toward each other.

Because when we do, there’s a very—

I mean, strong principles, yes—but like, softer hearts. More ability to think empathically.

I’m blown away by how much possibility there still is right now.

For us to lean more into love.

And like, how desperate we all are for that in a time of like—exhausting contempt. Exhausting strife.

And then just like you were saying—and then all the loneliness that follows.

Tim Shriver:

Well, that’s why people listen to you, Kate—because you’re reminding them of that.

And I think that’s, you know—we might not be able to change the culture. We might not be able to change the news or the algorithm. But we can create subcultures. And we can create countercultures.

And, you know, you and I both come from the Christian tradition.

You know how the Christian tradition was described in the early days?

It was described as The Way.

And people said, “Look at those people. What do they do? What’s going on over there?”

The dominant culture had—they had no power in the dominant culture.

But they created a counterculture.

It’s true of all religious traditions.

Some small group of people created a culture. And slowly, people walked by and said, “Wait a minute. What are they—? I want to look at—what are those people doing?”

And that’s what I see now.

I see so many countercultures.

And many of them are small. Some of them are big. Some of them are big companies that try to create a counterculture where people get treated with dignity.

Some of them are schools.

I mentioned the cops—thousands and thousands of law enforcement officers who donate millions of dollars—

Kate Bowler:

—to Special Olympics every year—

Tim Shriver:

—so that an athlete can get a chance to play on her team. Or run his race.

I mean, that’s America.

So I’m not willing to concede that love and compassion and human equality and human dignity are not part of this country.

They are.

They ARE this country.

That is the American spirit.

And it’s still alive. And in many ways, I think it’s growing.

And the dominant voices in the political ecosystem are not going to stop me from seeing that.

And I don’t think most people want to live in the world of that kind of contempt.

They want to live in the world of the people you have on, Kate.

In the world of faith.

In the world of hope.

Whether they’re religious or not is not the point.

But they want to believe.

In each other.

In themselves.

They want to be in a place where they can believe in themselves.

Like: “Wait, wait a minute. Do I—?”

Kate Bowler:

“Do I really matter?”

Tim Shriver:

Yes.

Someone tell me I matter, please.

“I think I do, but I’m not sure. I want to be someplace where someone tells me.”

Kate Bowler:

Yes. You do.

That’s right. That’s right.

Because we can’t be human without it.

Oh, Tim. I like you the most.

Tim Shriver:

Thanks, Kate.

Kate Bowler:

Most.

Tim Shriver:

Thanks for having me. I’m a huge fan.

Kate Bowler:

As Tim spoke, I just kept thinking about that story I loved as a kid—The Velveteen Rabbit.

Do you remember it?

There’s this little stuffed rabbit that just longs to be real.

But real, explains this other toy, the Skin Horse, isn’t about how you’re made.

It’s about what happens when you’re deeply loved.

Okay, so this is what the horse says:

“Generally, by the time you’re real, most of your hair has been loved off. And your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all because once you are real, you can’t be ugly—except to people who don’t understand.”

Ugh. I love that so much.

Because we certainly don’t feel shiny.

I think we can all relate to that.

But that’s how you become real, the horse says.

“When a child loves you for a long, long time. Not just to play with, but really loves you—then you become real.”

I just think that that’s what the transforming power of love sounds like.

That’s what Tim is calling us to recognize in ourselves and in the people around us.

That no matter what we look like.

How together we seem.

How we vote.

How much potential our high school guidance counselor said we had—

We have an inherent goodness.

An unshakable dignity, simply by being children of God.

Simply by being made good.

And then—when we start seeing ourselves that way—that is the mind and eyes of the divine.

We can’t help but be transformed by that kind of love.

That’s when we become real.

And then, weirdly, that’s when other people become real to us.

It’s just so strange to me that everyone is a stranger—until we learn how to be changed by love.

So if you need a little bit of a blessing to kind of stay in that place—a little of a lens of love—here’s one just for you:

Blessing:

Blessed are you who are tired of evaluating everyone like a spreadsheet.

Productive, impressive, worth the investment.

May you lay down the exhausting criteria

and instead notice the inherent belovedness

of the person next to you—and the person in the mirror.

So blessed are you.

Not because you’re nice—though you probably are—

but because love has wrecked you in the best possible way,

cracking open your heart to a way of seeing,

a way of being that changes you.

Because somewhere along the way,

you realized the very marrow of life is where God likes to hang out:

Among the overlooked and under-celebrated,

the disabled and dismissed,

the ones holding on by a thread

and the ones who show up anyway.

Among the spread-too-thin teachers

and the up-too-late volunteers,

and all the policymakers and parents

trying to squeeze compassion into systems that barely bend.

So may we all slow our pace to the speed of love.

The speed we can see with a bit more clarity—

All that is good.

And true.

And beautiful.

Beautiful—even the messy bits.

Especially the messy bits.

Because that is what it means to be real.

Kate Bowler:

Alright, gorgeous listeners.

Look, I just feel very lucky that you are here alongside of me.

I know that you don’t need any prodding to offer your great gifts to the world—but just in case—there are so many ways to partner with the incredible work of the Special Olympics.

I’ll put links in the show notes of today’s episode. I’ll also put in links to the Dignity Index so that you too can practice being very engaged with people who are not like you.

With maybe less bribery? I don’t know.

But I did sort of feel like I got Tim’s stamp of approval on that one.

This episode might be one that you want to share with friends. I would be so happy if you did.

We have the full thing available on YouTube if you want the link and see Tim’s beautiful hair.

I have absolutely no idea what he was talking about—his hair is spectacular.

You can also find more resources—so like Blessings and Reflections and Sassy Essays where I rant about cultural myths that I find irritating—over on Substack.

I’m at katebowler.substack.com

.

And hey, if there’s any chance that you liked this and want to leave us a review on Spotify or Apple, it would help so much for other people to find the show.

This episode was made possible because the Lilly Endowment has chosen to care deeply about Christian spirituality, and it gives us a chance to reflect on life and faith in service of God.

Thanks to my team who makes everything happen at Everything Happens:

Jessica Richie, Harriet Putman, Keith Weston, Anne Herring, Hayley Durett, Megan Cronkleton, Anna Fitzgerald Peterson, Iris Green, and Katherine Smith.

This is Everything Happens, with me, Kate Bowler.

Leave a Reply